|

Tall Timber Tales The Choice by Jeff Gilbert, MD July 26, 2013 | |||||

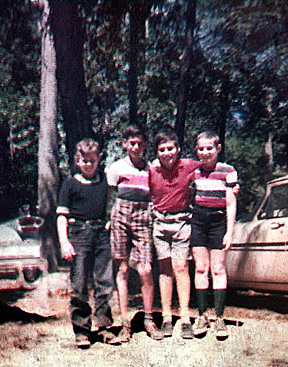

Upon reaching the age of six, my parents left the sands of Long Beach, Long Island, to spend summers in a bungalow rental on Mohegan Lake. For the next seven years, the last week of June meant the ending of school, and the upcoming move “upstate” to Boxer's Bungalows. Nothing more than two houses divided to provide space for five families, the bungalows served as a makeshift resort for those with limited funds for the summer holidays. The bungalows were compressed between two, much larger, bungalow colonies; the Sonoqua Club and Tall Timbers. A place where families could escape the heat and grime of New York, sending children to day camp, so mothers could play marathon mahjong, while fathers spent steamy time toiling the city. On weekends, families were reunited for barbecues and swimming in the spring-fed lake. On Sunday night, the larger bungalow colonies would feature a full-length, three-reel movie, projected on a large screen in a recreational hall known as a “casino.” Being somewhat friendly with Gail, the granddaughter of Mike and Nellie (owners of D&M Cozy Spot), assured me admission to the film of the week. Now, to get to Cozy Spot from Boxers was actually a short walk, but one that seemed much longer, because the roadway was an overgrown path frequented by skunks and snakes. Groups of us usually went together, but one particular Sunday, in July of 1961, while my friends Shelley Boxer, Terry and Stevie Wiederlight, and Ronnie Lulov were roasting marshmallows, I was inexplicably drawn to the showing of “The Last Angry Man.” A black and white film classic, starring Paul Muni and Luther Adler, it began at twilight with the casino half-filled with well-fed adults and a few crying infants. None of my friends made it over. The story told of Samuel Abelman, MD, an aging Jewish doctor, blessed with abundant medical skill but lacking social graces. Practicing in an abused section of Brooklyn, he was constantly assaulted by the worn down streets, walked by the indigent, the needy and the sick. His patients, never quite able to pay his meager fees but quick to demand his services. Dr. Abelman continually railed against the “galoots,” a term he frequently used to describe a person who thought that the world owed them something, but that they had to give nothing in order to get it. But Dr. Abelman stayed. Rejecting the religious pressures of a zealot father, he decided to pursue a medical career. Attending the NYU School of Medicine and earning his degree, he saw his classmates advance to lucrative practices while he stayed behind in Brooklyn, toiling with the poor. Dr. Max Vogel, a medical school classmate who specialized in cardiology, opened an office on Park Avenue, and cared for the affluent hearts of New York’s upper east side, was Abelman’s closest friend. Max would plead with Sam to leave the chaos of general practice and join the faculty of a prestigious teaching hospital. He knew that Dr. Abelman’s skills were well above those of the other “medical men.” But Dr. Abelman stayed. One particular patient was an unappreciative, neighborhood tough named Josh. Forcibly brought to the office by his mother, Josh was very ill. Dr. Abelman felt the boy's seizures were being caused by a brain tumor. But Josh was wild and of the streets, and rejected all offers of help. Suffering a seizure, after being arrested and incarcerated in a precinct jail cell, Josh called out for Dr. Abelman to come and help him. On his way up the long steep precinct staircase; sharp, crushing pains pierced Dr. Abelman's chest. He had suffered a heart attack, causing him to collapse. Taken to his bed, Sam quoted Henry David Thoreau, saying “Why should we be in such haste to succeed, in such desperate enterprises? If a man does not keep pace with his companions, perhaps it is because he hears a different drummer. Let him step to the music which he hears. However measured or far away.” Shortly after, he struggled for breath and despite the valiant efforts of Dr. Vogel, Sam died in Max’s arms. Dr. Vogel filled out the death certificate and said: “cause of death; coronary occlusion. Cause of death; fighting the battles of others.” The movie ended with Dr. Abelman's nephew, Myron, walking to the window and with the rain assaulting the street, turning off the light in the sign that for years read Samuel Abelman, MD. The casino lights came on, the reels were rewound and I sat still, overwhelmed with sadness for what I had just seen. I had formed a strange, unexpected attachment to this eccentric old medical relic who carried a black leather handgrip bag. I felt that I knew him, that he was a part of me. I had wanted Dr. Abelman to keep on living and working and curing and caring. But it was just a movie and it had to end. Now it was late and very dark and I was alone. Being frightened, and only 10 years old, I thought that a smart approach would be to bargain with God. The deal I made was that if I got safely back to my bungalow bed, I promised that I would become a doctor just like Dr. Ableman and practice in a neighborhood like the one he had endured. Fifteen minutes later I was transported back to the bungalow, now facing a new problem. Furious with me for staying out so late, knowing that I had to get up early to go to camp, my mother had locked me out. She refused to open the door, leaving me to sit on the steps. Alternately pleading with her to open the door, and telling her of this wondrous film, her position began to soften. I shared with her the feeling I’d had of knowing Dr. Abelman. She shed light on my confusion by telling me that years before, her father and mother, Dr. William and Rebecca Silverstein, had owned a home on Long Beach and had as next door neighbors Dr. & Mrs. Greenberg. Their son, Gerald, became a writer and authored the book “The Last Angry Man.” Gerald had used the lives of his father, Dr. Greenburg and my grandfather, Dr. Silverstein, to create the character of Dr. Samuel Abelman. Having heard from my grandfather stories of his childhood days in Brooklyn with his religiously dogmatic father, and of his struggles at NYU Medical School, and of his courting my grandmother, I clearly understood my kinship with Dr. Abelman.

The book was written in 1957, the movie was made in 1959, and by 1964, as the Yankees were losing the World Series to the St. Louis Cardinals, thoughts of my bargain on the pathway were distant ones indeed.

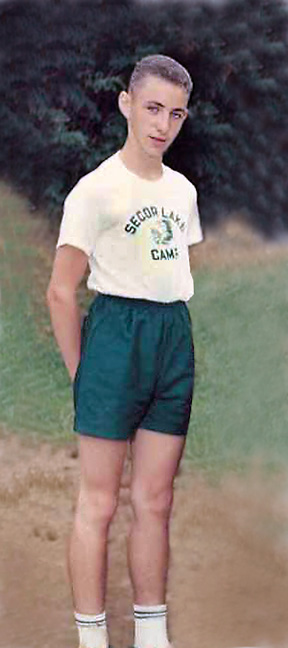

On an unusually hot spring day, his car ran out of gas on the way to the jail. Carrying a heavy can of gasoline for a mile or so he began having chest pains and was taken to the Bronx Hospital. He had suffered a heart attack. His friend and former classmate, Dr. Ben Littman, a cardiologist, began to care for him. On April 15, 1966, as I was preparing my baseball glove for a softball game with some friends, Easter recess came to a halt. The telephone rang in the hallway of our apartment on Walton Avenue in the Bronx. Dr. Littman was telling me that my grandfather had just passed away in his arms, succumbing to the damage of the infarction. Hanging up the phone, I began to cry. Crying for losing my grandpa but also remembering now, how five years before, Dr. Abelman had died. On his way to a jail, having his heart give out in the arms of his doctor and friend. It had come to be, that 9 years after it was written, my grandfather died in the same way. As I stood alone before his open casket at the Park West Funeral Home in Manhattan, I talked with my gramps one last time. He promised me that he and Dr. Abelman would be with me always. At the time, I was 15 years old and finishing the 10th grade. I knew then that I would walk where they had already been. Graduating Taft High School and Lehman College both in the Bronx, I was accepted to study at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine. My Bronx career continued. Upon graduation from medical school, most of my classmates scattered across the U.S. to do their internships, but I knew I could not go. Instead, I chose to train at the Bronx Hospital, the place where I had been born and where my grandfather had practiced and died. Many times, when I was called upon to care for the sick, the indigent discards from the practices of others, my thoughts were of Dr. Abelman and of my gramps. These two medical men would be there with me, helping me to make the right diagnosis, and the right decisions. Guiding me in my care for my patients. They were always looking in on me, offering solutions where I had seen none. Later, when I chose to practice in the ghettos of Harlem and the South Bronx, my offices were filled with the same patients that Dr. Abelman had felt privileged to treat. He knew that he had been given a gift. So did I. I have often wondered how Gerald Green would feel if he knew how much his story had meant to me. For the past 38 years I have both practiced and taught medicine. Countless times I have found my students looking at me in odd ways, asking why I chose to practice with patients whom others considered to be the medical underclass. Some even told me that they considered me to be a peculiar sort. When first faced with their inquiries, I would start to tell them the story of Sam and Max and Myron and Josh, but I would stop. Finding my response to be defensive, somehow hoping to make them see me in a less odd way.

Now, when asked of my choices, but equipped with experience and age, I keep the story to myself. Only responding to them, “Why? Because I am the last angry man.”

Article © 2013, Jeff Gilbert, MD

Entire contents © 2024, Demian

Individuals own the rights to their own photos and writings. Demian Seattle, WA 206-935-1206 demian@buddybuddy.com |