|

Welcome to the Archive Version of the online On the Purple Circuit, which ran from 2000-2021. Bill Kaiser founded the Circuit as a newsletter in 1991, and, in 2000, Demian joined as co-editor. Demian programmed the site, expanded the scope of the Circuit, as well as retouched all the images. Demian needed to stop working on the Purple Circuit in order to realize his other projects, such as publishing the book “Operating Manual for Same-Sex Couples: Navigating the rules, rites & rights,” now available on Amazon, and to publishing his “Photo Stories by Demian” books based on his more than 6 decades as a photographer and writer. QueerWise and Michael Kearns have committed to offering a continuation of the Purple Circuit. The new Web address is purplecircuit.org. Bill Kaiser continues as editor and can be reached at purplecir@aol.com Bill and Demian express their appreciation for the hundreds of writers, directors, actors, and publicists who sent their articles and play data. They have toiled mightily to bring our gay, lesbian, trans, and feminist culture into public view, and appreciation. |

| Bill Kaiser, founder (1991), publisher, editor - purplecir@aol.com - 818-953-5096 Demian, associate editor (2000), Web builder, image retouch (since 2003) Contents © 2022, Purple Circuit, 921 N. Naomi St., Burbank, CA 91505 |

|

Turning Oral Histories into Performance by Bob Baker © August 27, 2004 Bob Baker |

|

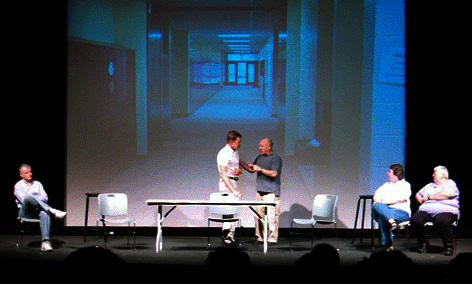

Bob Baker produced and directed “Stories to Tell.” He facilitated scripting this play from oral histories that were spoken by Clara Alderman, Bill Dawson, John Fournier, Margaret Jensen, and Larry Rubinstein (who also designed the sound and graphics). “Stories” ran on April 15-17, 19, 2004, at The Renberg Theater, Gay and Lesbian Center in Los Angeles, California. Bob’s background includes teaching in the Pierce College Theater Department (Los Angeles Community College District). This is an account of the process that Bob took in producing the project.

I had been retired from teaching theater for a number of years, and I was feeling some of the angst of retirement and being a single, gay man in my late sixties. During 2002-03 I had been attending a support group for senior men at the Los Angeles Gay and Lesbian Center. It was not group therapy, but, as I heard from each of these men weekly, a subtle and unexpected thing began to happen to me. While I was getting to know and have affection for these men, I somehow began to feel better about getting older myself. Occasionally, some of the men recounted incidents going back decades. These stories really grabbed me. It occurred to me that a wider audience should hear them. One particularly fascinating group member, Harry Bartron, was an actor-pantomimic in his eighties. He shared a lot of his writing with me, including a 120-page volume of e-mail printouts he had sent to his daughter during one year. Each e-mail related an incident in his life. Altogether, the collection was the story of his life from childhood to his mid thirties, told in vignettes, incidents, and anecdotes. I suggested to Harry that this material was potentially the basis for a performance piece for him; a one-man show that could include his mime, poetry, songs, and stories from his life. Harry, however, was reluctant to take on a project in which he was the total focus. What if more people were involved in such a project? I presented a proposal at the Los Angeles Gay and Lesbian Center for an “Oral History Project” aimed at transcribing oral histories of gay and lesbian seniors, leading to a dramatic production in which these same seniors would share their stories. I expected to commit at least a year to the project. The proposal was accepted. There were 15 participants at the first meeting, which was held at the Center on April 15, 2003. During the rest of the year, we had 35 two-hour storytelling workshop sessions. Twenty-nine participants (25 men and 4 women) attended one or more meetings, averaging 12 participants per session. ——— Preparation Before beginning the workshops, I researched techniques for gathering oral histories and making transcriptions. I also planned some exercises and activities for the first several workshops. The first two meetings involved group orientation exercises that I hoped would painlessly get us to telling personal stories by the third session. One technique was to split into groups of two people, each person taking turns interviewing the other, then reporting back to the group as a whole. Talking in front of a group about intimate matters takes lots of courage. Usually, oral histories are gathered in one-on-one settings with just the subject and the interviewer. We were going to be doing something different. Early on I decided to participate fully in the process; telling, recording, and transcribing my own stories. I had to experience what I expected others to do. And I also wanted to avoid taking on any kind of traditional teacher’s role. This turned out to be a wise direction for me. Not only did I gain the benefits and insights of full participation; I better understood problems of the process as they surfaced. Key elements:

——— Primary principle Since we were dealing with oral history, I stressed that stories should be told, not read, regardless of the way a storyteller might prepare. I wanted to avoid “literary readings,” which, I felt, would work against the vitality of the group dynamic. The goal was not a performance, but rather a sharing of an experience. I urged storytellers to make eye contact with their listeners and concentrate on telling the story in as much detail as they could remember. If vital information was forgotten, it could be brought out later in discussion. Some participants did briefly refer to notes or lists in telling a story, but this did not become a problem. ——— Taping For taping at the third meeting, I had the following:

At the beginning of the third workshop there was demonstration of the use of the two tape recorders and the process for taping. One recorder was used to make a master tape that contained all recordings. The other recorder was used by individual members to make tapes for use in transcribing or for other personal use. I kept records attached to each master tape:

——— A Boy’s Own Story In preparing for the third meeting with my story of an early family outing, I had some insights and revelations about my own family dynamic. This motivated me to start sharing my stories with my sister via e-mail, as had Harry Bartron with his daughter. Thus began a dialogue in which my sister and I compared our experiences on a regular basis. A whole new level of understanding was the result. I soon found I was not the only person in the workshop having such experiences. Starting with that third meeting, from time to time others reported to the group their own insights. ——— Meeting Techniques By the end of the first taping, the group had determined that we needed to limit storytelling to seven minutes for each participant. I got a timer that was then used for all sessions. I collected transcriptions of the tapes on my computer in a file for each participant. The task was easy with e-mail, and fortunately, all but one storyteller were able to send their transcriptions this way. One member gave me typed copies that I scanned into my computer via optical character recognition. Transcribing is time-consuming, and there was a lot of discussion about it. One storyteller diligently transcribed word for word, indicating pauses and non-lingual utterances. This was the most difficult method. These transcriptions were marvelously effective realistic pieces of dialogue. Some participants chose to edit transcriptions, making changes and additions as needed. Other storytellers preferred to write their stories out in full before a session, and then create a transcription by selecting and combining elements from the draft and the tape. ——— A Revelation A number of participants did not want to transcribe their stories; for them the most important thing was to tell their stories and listen to those of others. It became clear to me that the major benefit of the workshop was in the storytelling. My goal had been a performance, but for a while that took a back seat to the importance of the group experience. ——— Use of Topics For our second and third days of taping I suggested a few topics such as “early erotic experiences” and “early experiences of homophobia.” A number of men said they had not experienced homophobia; however, by the end of the session some of these same men remembered instances of their own internalized homophobia. This moved the group into a very stimulating and informative discussion. At the fifth session, I distributed a long list of topics and questions to stimulate story ideas. Participants then selected their own topics for the rest of the year. If a staged production is the goal, I would suggest using specific topics in order to speed up the process. In our case, we were not in a hurry. From the beginning, I wanted to see participants grow in storytelling skills, but I did not want to lecture or teach the topic. I felt that good use of specifics — in narrative and description — would afford stronger communication. In the workshop I often asked questions about details of a story or referred to specific details used by the storytellers, thus teaching this aspect of storytelling indirectly. There were short breaks whenever recorders were passed to the next speaker and their tape inserted. This provided a natural time for casual discussion about the previous story. Inquiry and comments about details of a story naturally became a part these exchanges. There was no criticism. ——— A More In-depth Approach By mid-May, I realized that the seven-minute time limit would hinder complete telling of longer, more complicated stories. Not wanting people to rush or generalize in telling a story nor to limit their choices, I suggested that storytellers estimate how long it would take to tell a story, then find a way to break long stories into short episodes or installations. I think this episodic approach encouraged the development of specifics. And it may have been an influence in the episodic approach we came to use in the performance. I continued to collect transcriptions on my computer and on May 30, 2003, we distributed them in our first printout — “Digest One” — to members of the workshop and other interested parties. By June, the group had settled into a very friendly and comfortable routine with the usual 12-to-15 participants at most meetings, which ran two hours. These first two months were an exploration. Solutions to problems were found as they arose. By the second month, the uncertainty of the path was accepted. By the summer, the group seemed to run itself. We continued the distribution of transcripts with “Digest Two,” “Digest Three,” and “Digest Four,” in September, October, and December of 2003. ——— Changing Gears As our collection of transcriptions grew, it was clear that we could create a dramatic performance. I knew I did not want a reading, but rather a memorized, rehearsed, and integrated group performance. At this point, I learned that Tim Miller was offering a workshop in Truro, Massachusetts. I grabbed the opportunity. It was just what I needed. In his workshop Tim stresses elements of sound and physical movement as a source for finding a story. With my seniors, I had concentrated entirely on the verbal aspects of telling the story, and on elements that would primarily help in developing the details of a script. I saw the value of Tim’s approach and knew that I would do this with my seniors as well. Also with Tim, we often worked together in groups of two or three, helping one another in the presentation of our stories. I saw how varied, and effective, this could be in what I wanted to do. ——— Continuing the Process By October, we had three volumes of transcriptions. It was time to create a script. Eventually, five participants wanted to work on a performance piece, using their material in a group effort. It was determined that the regular weekly storytelling sessions would continue until January, 2004. Outside of these sessions, I continued to work with the performers on a first draft of a script. We wanted to reveal aspects of the performers’ lives through specific events, relationships, and experiences. We attempted to keep a feeling of variety and movement, staying with a speaker for short periods. Some stories were cut into episodes. Then we switched from performer to performer in an irregular pattern, developing complete stories in separate short interludes. It was a cinematic approach, cutting back and forth among the performers as if through a series of film edits. In this manner, seemingly ordinary incidents of life often took on a special value by being emphasized or framed in these short, separate, storytelling passages. ——— Rehearsal As planned, we began rehearsals in January, 2004. Work continued on the script with revision and the addition of new stories. The rehearsal process itself required a lot of patience and sensitivity from all of us. I had to keep in mind that these stories were the intimate life and property of these performers. Additionally, most of the performers had never acted, or had not acted in years. The script was still in progress, and the form of performance we used put us on an untried path. At the same time, the actors craved decision, consistency, and permanence. My job demanded objectivity, flexibility, understanding, and calm patience. The primary strength of the production was that these were true stories told by the people who lived them. We used storytelling devices, including straight narrative, story theater approaches, dialogue, dramatization, and characterization. The storytellers periodically played parts in one another’s stories. ——— Set Our set consisted of a rectangular table center stage, chairs and stools scattered about, and a very large projection screen filling the back wall of the playing space. ——— Presentation Style While many sections of dialogue between two characters were done with the characters facing each other, some dialogue was addressed directly to the audience. For instance, for a physical confrontation that ends with one character being knocked to the ground by another, both characters faced front, speaking and gesturing straight toward the audience, as if to the other character. We attempted to get as much physical action into the piece as possible. When performing solo narration the actor was encouraged to think of being in the scene as the story was told. Sometimes the actor might suggest some bits of the action or actually go through it. Most narration was spoken directly to the audience. The simple set was used in a fluid, flexible way. There were no physical props; all were pantomimed. Actors moved about, suggesting locale by action or words, sometimes several different places in a single narrative. Often the graphic on the rear screen showed the place. The table became a psychiatrist’s couch, a sofa, the bleachers at a circus, a dining room table, a conference table, several different desks, and the communion rail at a church. ——— Performance Elements In rehearsal we experimented with various approaches to performance. One matter of concern was the style of performance to be taken by an actor when playing a part in the story of another player. We determined that for this production the assisting player should not draw unnecessary attention by his or her performance style. For instance, exaggeration or caricature did not work for these pieces in this particular production. On the other hand, when a performer was doing his or her own material, the performance choices depended on the actor’s personality. As director, I encouraged the actor go to his or her limits. However, I found that for a sense of truth these choices had to come out of the real persona of the performer. What was right for one might be out of place or excessive for another. The objective of the performers was to communicate these stories. They were not actors playing roles; they were the real witnesses. Therefore, our performance emphasis was on the actor-audience relationship. Energy and clarity were required in the deep, 300-seat Renberg Theater. It was important for the performer to place his or her attention on the audience, to develop a desire to tell the story, and to focus attention on making sure that the details were heard and understood. As we got closer to our performance date, these actor objectives became primary. ——— A-V component Cast member Larry Rubinstein designed a graphics and sound accompaniment in PowerPoint, utilizing a dense, witty, and imaginative combination of authentic photographs, as well as found and created images. These were projected on the huge screen. The result was much more than simple documentation. The graphics helped us to maintain a sense of objectivity in the whole proceeding, and they were a great aid in achieving clarity. Most important, however, was the way the graphics and sound moved the performance along, marking changes of mood and rhythm and adding humor. This was an invaluable contribution. At minimum, I would recommend the use of authentic photographs to augment a live performance. ——— Performance We opened one year after the first meeting of the Oral History Project, running four performances, one of which was for two Oasis schools (alternate high schools in Los Angeles for gay and lesbian youths). During my high school days in the 50s, I was haunted by my own homophobia. I can only imagine how that might have shifted if I had the fortune to see five old homosexual men and women telling me about their lives. What a life-changing event that might have been. It is important for the seniors to be heard, especially by younger gays and lesbians. An intergenerational divide exists in the gay community, just as it does in the non-gay community. To hear gay and lesbian seniors telling stories of there lives from the last half of the 20th century is to hear first-hand reports that speak of amazing changes in what it means to be lesbian or gay. A talking-heads documentary will never have the power that is offered by a live theater event in which you are in the same room with the people who lived these events. ——— Conclusion Studies have shown that people who reveal a lot about themselves tend to have higher self-esteem. Also, people who have high self-esteem tend to reveal a lot about themselves. Self-revelation = self-esteem. Self-esteem = self-revelation. This speaks especially to many gays and lesbians who know what it is like to keep quiet about their sexual identity. To counter the silence, one can tell stories. There is liberation for a storyteller and potential power for an audience. |